Sawed or Saved – The Village that created Franconia Notch State Park – by Ham Mehlman

December 19, 2024

Posted in

On August 3, 1923, an inferno, culminating with the explosion of 800 gallons of fuel, leveled Profile House, a grand hotel located under the gaze of the “Old Man”, between Profile Lake and Echo Lakes at the top of the Notch. The fire burned for only four hours, but that fire set in motion a remarkable five-year campaign to preserve under public ownership one of the most sublime and featured landscapes in the Northeast, Franconia Notch.

Profile House was a product of the gilded age and the Notch was something akin to Newport, RI, for the wealthy, outdoors set of the day. In its final incarnation, Profile House could accommodate 600 guests, boasted a dining room for 400, and could board 350 horses. It built a 9.5 mile private rail line from “Bethlehem Junction” to bring guests to the grounds. The Profile House also maintained a farm with its own dairy cows, a greenhouse, a power plant, a steam launch and the most modern conveniences including indoor plumbing and electricity. It was pretty much a self-contained playground of the grandest order.

But its main asset was the Notch itself: Profile House owned Franconia Notch. Over the years since opening in 1853, Profile House’s principal owners, Richard Taft, until his death in 1881, and Charles Greenleaf, until selling to Frank H. Abbot and Son in

1922, accumulated 6,157 acres stretching seven miles along both sides of the Daniel Webster Highway from the town of Lincoln north to the far side of the current Mittersill property. The towering Eagle Cliffs of Mt. Lafayette and the severe granite face of Cannon framed a sublime vista harboring popular natural curiosities including Flume gorge, the Pool, the

Basin, three glacial lakes, huge glacial erratics and miles of hiking trails, all under the “severe expression” of the “Old Man.” In preserving the Notch in its natural state, Taft and Greenleaf were early pioneers in profiting from their version of eco-tourism in a period when most saw economic value only in exploiting Nature for resources, principally timber in this area of NH. Travel brochures dubbed the Notch “The little Yosemite.” By the 1920’s, as the Notch opened its access to the public, more than 100,000 people a year were paying admission just to explore the Flume.

The fire was a financial disaster for the Abbotts. They had borrowed to purchase Profile House just a year earlier. They shared in the vision

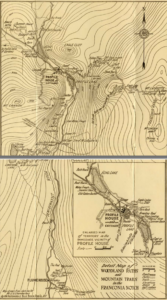

Map of Notch from late 1870’s

lled, lying in the towns of Franconia and Lincoln, as a forest reservation and state park.” The act provided for “the governor with the advice of council … to acquire on behalf of the state by purchase, if in their judgment they can be purchased at a fair valuation, such lands Iying in Franconia and Lincoln, including all or part of the properties of the Profile and Flume Hotels Company and the wood and timber standing thereon and constituting a part of the Franconia Notch and Flume properties, so called, as the governor and council, aided by the advice of the Forestry Commission, may deem necessary for the preservation of the forests and scenery, and to accept deeds thereof in the name of the state.” The legislature allocated $200,000 for the purchase.

of preserving the Notch and were amenable to creating a state park with their land holdings – but for a price. And timber interests made ready buyers or lessors for the mature stands of beach, birch, chestnut and white pine.

In the 1925, the NH State Legislature unanimously approved “An act to preserve for the acquisition by the state of the Franconia Notch, so ca

But they needed $400,000.

By 1923 there were many forces allied in the goal of conserving natural spaces and they quickly rallied, spearheaded by The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests led by Phillip Ayres. The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (SPNHF) was formed in Concord, NH in February 1901 “…to preserve the forests of New Hampshire, to protect its scenery, to encourage the building of good roads, and to cooperate in other measures of public improvement in the State.” They had been instrumental in securing passage of the Weeks Act in 1911 providing for the federal acquisition of “forest lands on the headwaters of navigable streams.” The Weeks Act is the enabling legislation for the entire National Forest network and enabled the establishment of the White Mountain National Forest. SPNHF also led efforts for the state to acquire properties such as Crawford Notch in 2013 and land around Mt. Sunapee in 2011. Among its early leaders was Allen Chamberlain, journalist and a future president of the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC).

Parcels creating original FNSP outlined against current boundaries (lemon green area)

On September 11, 1924, “the SPNHF’s Executive Committee took up the cause and set a meeting with Karl Abbott eventually agreeing to purchase all the Abbott property for $400,000. SPNHF convinced Governor Winant, after some haranguing, to support legislation for $200,000 on the condition that SPNHF would raise the other $200,000. This was a significant commitment, the equivalent of approximately $3.5 million in today’s dollars.

In 1926, Boston financier James J. Storrow and a founding member of SPNHF, pledged $100,000 significantly brightening the prospects. The sources for the remaining $100,000 are a remarkable tribute to leadership and collective effort. They faced a March 1928 deadline to complete the fundraising, later extended to June 1, 1928. Edward Tuck, benefactor of Dartmouth, sent a check for $10,000. The Appalachian Mountain club contributed $7,000.

But it would fall to the New Hampshire Federation of Women’s Clubs (NHFWC) to raise the bulk of the remaining funds. NHFWC had a particular long-standing interest in conservation. Ellen McRoberts Mason was a founding member of SPNHF back in 1901 and now chaired the Forestry Committee for NHFWC. Through remarkable organization and dedication, NHFWC would ultimately raise about $70,000 with $7,000 from other

states. Support was broad-based, ultimately receiving donations from more than 15,000 contributors. The club set goals for its 12,000 members in 151 New Hampshire towns. With SPNHF they launched a campaign to “sell” trees for $1.00 in return for a “certificate of Purchase.” “The Notch would be saved tree by tree.”

On June 15, 1928, the SPNHF reported that “On June seventh arrangements were concluded for the acquisition of the entire Franconia Notch property, including the Old Man of the Mountain, Echo and Profile Lakes, the Flume, and about six thousand acres of land in Franconia and Lincoln. This was only possible through the prompt and generous response of the fifteen thousand contributors to our fund…. The appreciation and thanks of the Society are due to those public-spirited citizens whose contributions have made it possible to bring this marvelous property into public ownership and save it for all time from destructive lumbering and exploitation for profit. In particular the State Federation of Women’s Clubs and other organizations which have co-operated in this project with the Society are entitled to the gratitude of the State and forest lovers everywhere for their effective leadership in the campaign which has been so successfully concluded.”

Today, Franconia Notch State Park is 6,807 acres. Per agreement, in 1947 the SPNHF turned over the 913 acres it managed, to be included in the park. Over time, the state added terrain particularly west of the Basin, at the southern end in Lincoln and to the western portions of the Cannon and Mittersill ski areas. It also transferred several parcels on the east side to US Forest Service jurisdiction.

The following articles might be helpful if you are interested in learning more about the effort to establish Franconia Notch State Park:

- “The Preservation of Franconia Notch: The Old Man’s Legacy,” Kimberly Jarvis. Historical New Hampshire, Fall/Winter 2003 vol 58, no’s 3 & 4.

- Franconia Notch: “Sawed or Saved?” Howard Mansfield, Forest Notes, Autumn 1998

- “The New Hampshire Women Who Launched a Conservation Movement,” Emily Newcombe,Governing, March 28, 2022.